Our tax system asks too much of those with little, and too little of those with much.

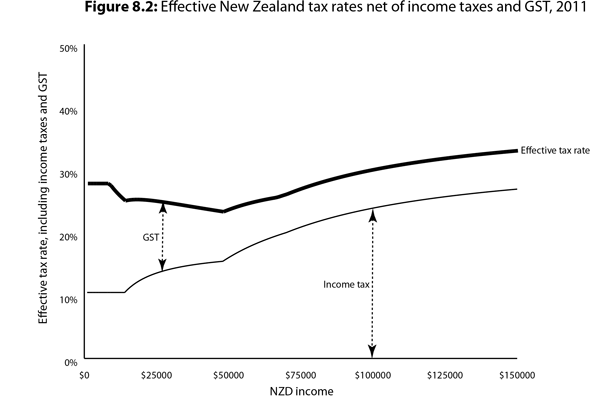

You may recall that our tax system got a major overhaul in the 2010 Budget, with income tax rates going down while GST went up. This changed substantially the shares of tax revenue being paid by poor people and by rich people. Poor people pay for more of the government than they used to, while rich people pay for less.

Under this new structure, low income New Zealanders also have to pay more total tax, combining income tax and GST, than they would pay in other rich countries, while high income New Zealanders pay a lot less.

This calls into question National’s claim that its goal was to kickstart the economy by helping everyday folk get ahead. If that is the goal, why hit ordinary folk with a bigger tax bill than they would get elsewhere, while giving the elite a smaller one?

Even before 2010, New Zealand’s GST was one of the biggest consumption taxes in the OECD. Our GST is big, despite its quite low maximum rate, because we charge it on just about everything. Most other countries give GST discounts, sometimes waiving the tax entirely, on items like non-restaurant food, public transport, books, some health and education expenses, and so on. Now that GST has gone up from 12.5% to 15%, it is close to the biggest consumption tax in the developed world.

This matters because consumption taxes are regressive. That is, poor people lose a bigger proportion of their income in GST than rich people. New Zealand’s consumption tax is especially regressive, because many of the tax reductions that other countries provide are for goods and services more likely to be bought by people with modest incomes.

To balance that out, we might expect an unusually progressive income tax system, right? Sadly, no. At very low incomes, New Zealand’s taxes are a little above the OECD average, as many OECD countries, unlike New Zealand, have an initial zero tax bracket or personal exemption.

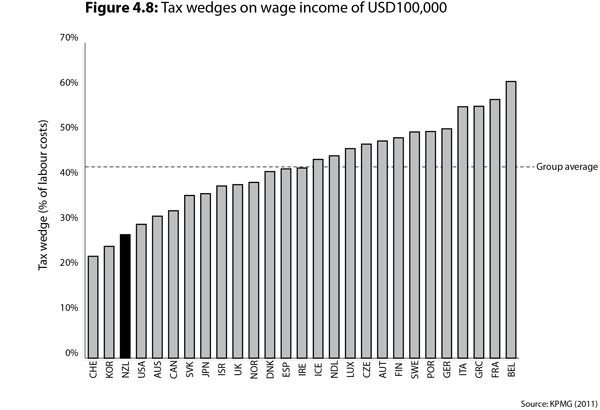

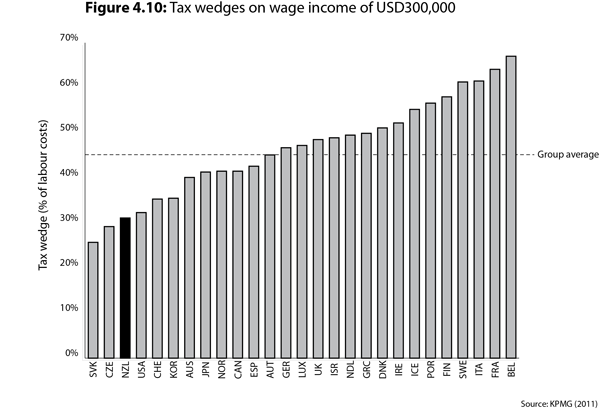

But for high incomes, our overall “tax wedge” (which includes all income taxes and social security taxes, whether nominally employee-paid or niminally employer-paid) is the lowest in the developed world. And while it is true that New Zealand’s top rate kicks in earlier than in some other countries, KPMG calculated that New Zealand’s overall tax wedge on incomes of US$100,000 and US$300,000 are among the three lowest in the OECD.

This means our income taxes are less progressive than many others in the developed world, too.

Each of these individual elements has a reasonable justification when considered on its own. Our GST is big because it is efficient, with no deductions that sometimes create tricky boundary disputes. Efficiency is a good thing. And our income tax is fairly flat and also low at the top end in order to provide the maximum reward for success and the least distortion to pure economic incentives. Distortion is a bad thing, and getting incentives right is good.

But when we are assessing the tax system as a whole, we need to consider these elements not individually but in combination. There are goods and evils that an entire tax system can produce quite apart from technical issues of efficiency, distortion, and so on in any particular tax.

A heavy, regressive consumption tax combined with a light, not very progressive income tax is not a recipe for helping ordinary New Zealanders get ahead. Our tax system, as a whole, keeps ordinary folk scratching to make ends meet, while charging New Zealand’s elite relatively little. In fact, the overall rate of tax that a low income person pays is little different to that of a rich person.

People on low incomes pay more overall tax, combining income and consumption taxes, in New Zealand than they would in Australia or the UK (or many other countries). But people on high incomes pay less here than they would pay in either of those places, or almost anywhere else in the OECD.

If you were to factor in capital gains taxes, or lack thereof in New Zealand, the disparity would be bigger again.

This structure causes many bad outcomes, including:

- In welfare terms, it is an inefficient way to raise revenue for the social services New Zealanders overwhelmingly want the government to provide.

- The relatively flat overall tax scale is relatively inefficient at stimulating demand in the economy.

- This tax structure limits social mobility, and works against the idea that hard work and talent are the only causes of success in this world.

Our tax structure makes it easier for those who are already ahead to stay ahead, and makes it harder for those with few resources to catch up. New Zealanders pride themselves on living in a meritocracy, but this set of tax policies makes New Zealand society less merit-based than it once was, or than it could be tomorrow.

One obvious solution is to substantially cut income taxes at the low end.

But if we did that there would be not enough money to fund social services. That would lead to large increases in user charges, which surveys show New Zealanders oppose strongly. We need better solutions than this, less like a lolly scramble and more like an actual meal. That is the challenge for the opposition parties.

Note: The charts in this post are from my book The New New Zealand Tax System, which also provides data and more explanation around all the figures I cite here.