Salaried progressives in Wellington should be prepared to share in the nation’s pain for their own self-preservation.

Look at this painting by Jean-François Millet. It shows two French peasants stopping to pray the Angelus while tending to their potato crop in the middle of the 19th century. I think it’s lovely and I keep a copy in my office

JEAN-FRANÇOIS MILLET - El Ángelus (Museo de Orsay, 1857-1859

By modern standards, these people were much more ignorant than we are. But the chances are, however, that these farmers had a much more intuitive grasp of how an economy works than we moderns do in an era of deracinated specialisation.

French peasants may not have had degrees in social policy, but they knew that their survival depended the useful things they could provide for themselves and others. They understood that unforeseen disruptions that got in the way of useful output could mean penury. That fear was surely part of the reason they were so pious.

When I used to work in an upscale food store in Wellington, shoppers would complain about the outrageous price of things like capsicums in June and July. There was no understanding about the effect of the seasons on the supply of fresh produce. The simple labourers of the 19th century would have known better.

The late Tom Wolfe once wrote about the “Great Re-Learning” that occurred consequent to the relaxation of hygiene by hippies in the 1960s. Diseases unseen for centuries made an unwelcome but insistent comeback. Nature had not gone away, it had only been temporarily managed.

As a result of the COVID 19 lockdown, economic activity in this country has been severely curtailed. People aren’t producing and exchanging useful things at the volume and velocity on which we have come to depend. National productivity has taken a punch in gut like nothing else in the living memory of all but the very oldest New Zealanders.

This is necessary to save lives. Human life is sacred and it is the first duty of government to protect jt. And if generalised hardship is the price for that then so be it. Those taking other approaches may well rue their decisions before long.

But with most people now working for large employers, a serious disconnect has developed between what we do in our job and why that results in our salary being paid. For anyone working for a big organisation, the money just tends to turn up in a bank account every fortnight no matter what they do or don’t do. A week of no production is just sucked up by the system.

For those lucky enough to have well-paying state sector jobs, the connection between productivity and salary is even more remote. They don’t need customers to keep their job because the government can just take and borrow what it wants to keep the money going. Not forever, perhaps, but there’s a great deal of ruin in a nation.

If the lockdown continues beyond four weeks, however, some people are going to be in for a real shock.

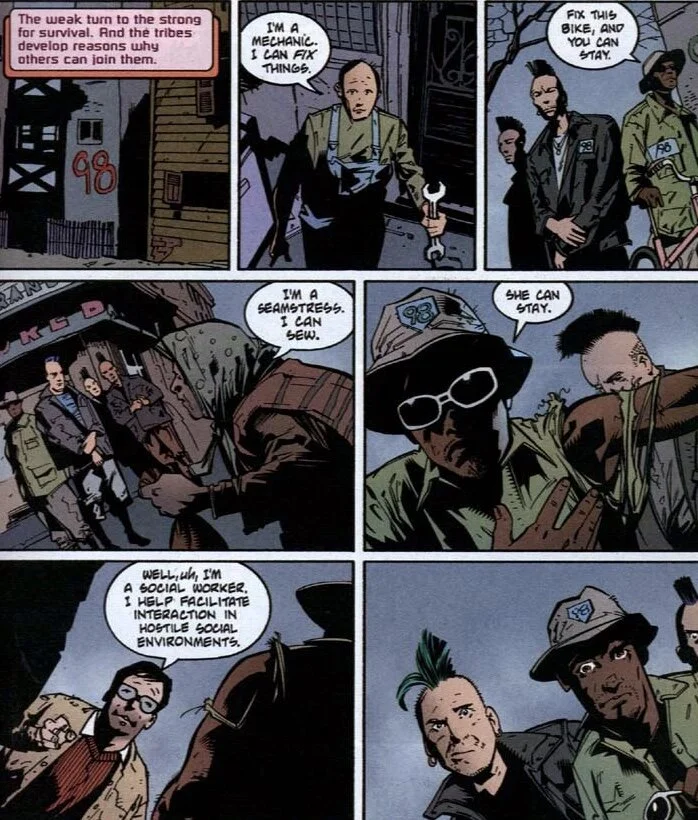

The panel below is taken from No Man’s Land, the epic Batman comic book arc that involved Gotham City being abandoned by the authorities in the wake of a terrible earthquake.

From Batman: No Man’s Land Volume 1,.Written by Bob Gale And Devin K. Grayson; Art by Alex Maleev, Dale Eaglesham and others. DC Comics, 1999.

Now, social workers obviously have a lot of value. Their jobs are essential in a modern society and we would all be much poorer without them. However, the role such people have is a secondary one compared to other jobs that provide the direct necessities of life. We can have them only when the more immediate needs are provided for.

This goes doubly for people who make their living through peddling ideas. if those still trying to survive in Gotham may not have had a lot of need for a social worker, they’d have even less for a policy analyst.

Now clearly we are a long way from the collapse of law and order in New Zealand. Not only are we not there, we can’t see there from here.

But what is interesting is that, instead of worrying about the economic shutdown, many in the idea producing caste seem to see the crisis as an opportunity to re-order life around their opinions and priorities. And anybody who is worried about the economy - which really just amounts to good snd services being made and distributed - is at the moment being lambasted on social media as an Ayn Rand wannabe.

This is beyond foolish. The utopian idea of a world in which prosperity and the need to work for it not new. There are good reasons why, every time it has been tried, the result has tended to be exploitative in practice.

From all reports, for example, a determination has been made that central government employees should be exempt from the economic suffering the rest of us must endure. Public servants sent home with no work to complete (or no means of completing it) will continue to receive full pay in the expectation, perhaps, that they attend a few online professional development webinars. The great money tap connecting Wellington to the rest the country is to remain on full blast for the duration.

The Hingrr Games, Liongate, 2012

It seems that, in the event of a prolonged economic slump, the country will begin to resemble the world of the Hunger Games. There will be a brightly lit Capitol shining with the vibrancy of relative prosperity despite the oroduction of very little that is tangible. And there will be the rest of the country, which will have to get by on a much reduced standard of living.

If you talk to salaried progressives about the things ahead of us, there is a renewed hope of workers finally turning against their bosses and embracing the economic platform of the Green Party. If we have a depression, however, the hated bosses are going to be as ruined as everybody else. It won’t be bankrupted pub owners who are the target of popular discontent.

In fact, the only people who seem to have an assurance of remaining well-fed are the publicly-funded ideas merchants whose contributions to our collective wellbeing are so vague and remote. In other words, the people who seem most blasé about what happens to the economy are likely to be those least affected by its destruction. Perhaps they should be less gleeful about the prospect of an upended social order in response to that.

All I know is that if it was me I might be a little more eager to demonstrate sharing in the general pain. For the better paid, a 20 per cent cut in pay now seems like a pretty sensible precaution. It might save much later down the track.

Otherwise, the ideas class may soon learn that the peasantry can find many uses for their pitchforks.

[Note: edits for typos and clarity]