If we think about our taxes one at a time, we might think one thing. But if you consider them all together, a different picture emerges.

Combinations matter, and can make complex things either better or worse than the sum of the individual parts. What’s that? You want a folksy introductory example? OK:

Do you like chorizo? How about asparagus? And sorbet? Yes? Then you’ll love my new chorizo and asparagus sorbet! Wait, where are you going…

Government is like that, too. You can have a set of individual policies that look really neat by themselves, but when you put them all together they turn into an unattractive mess.

I think our tax policy exemplifies this pretty well. The individual component parts are designed in particular ways, often with a powerful individual justification:

- Our GST has no exceptions because that is very efficient;

- Our income / social security tax has low rates and few exceptions for efficiency and to provide powerful incentives for entrepreneurship;

- We have no capital gains tax as a further incentive for entrepreneurship;

- Our corporate tax is designed with few loopholes and with full write-offs against personal taxes to maximize efficiency and minimize distortion.

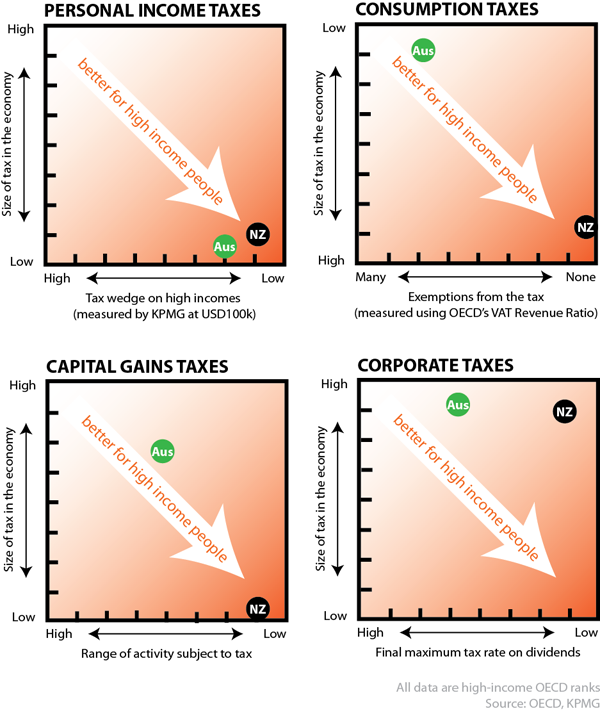

Considered separately, these reasons can be compelling. But when you examine the tax system as a whole, you see that our system has become dangerously unbalanced. Consider the chart below, which combines data on New Zealand’s OECD rank in two important aspects of each of the four taxes I mention above. Most of the raw data are available in my book on this stuff. Australian rankings are also provided for comparison.

(Certain combinations of these two elements favour low income earners relative to high income earners, others to the converse. Most of the orderings in the chart should be fairly intuitive, with one exception. I rank large GST-style consumption taxes as being good for high-income people, and small ones as good for low-income people. This is because, whether you think of the GST as regressive or flat – see recent debate here and here and here and here – GST serves to flatten out the overall tax system, because most other taxes are progressive. The bigger the GST, the flatter the overall tax system, which – speaking relatively – is good for people with high incomes.)

The chart shows that New Zealand’s combination of tax policies is relatively very favourable to people with high incomes, and relatively very unfavourable to people with low incomes. Across the board, New Zealanders with low incomes are asked to shoulder a greater proportion of the tax burden than are low income earners in other similar countries. And almost across the board, high income people are asked for less.

In contrast, Australia has a more diverse range of tax policies – its income tax policy is very favourable to high income earners, while its consumption tax and consumption tax policy is more favourable to low income earners.

Some might argue that this logic of combinations is helpful, but that my particular analysis is problematic because it doesn't combine at a high enough level. Why stop at “tax policy?” Why not examine “public policy” instead?

I do not have the data to do that broad task systematically, but thinking about it even casually confirms that something is amiss in New Zealand.

In order to balance out a tax system that is, relative to other countries, very favourable to people with high incomes, we would need a delivery system for public services that was not at all favourable to people on high incomes. But that is clearly not the system of service delivery we have in New Zealand. A few examples:

- Our system of additional family support (Working for Families) does not give family-based support the poorest families - those on benefits, but does support families reaching quite a long way up the income scale.

- Our policy on retirement income does not provide for asset tests or means tests, meaning high income people will get a public pension in New Zealand when they might not in some other countries;

- Our public schools are of a high enough quality to be attractive to high income families (more so than, say, the UK or Australia), and New Zealand does not have income-tested fees for public schooling, either.

- Our tertiary education system features a generous student loan scheme, benefitting students who disproportionately come from high income families with billions of dollars of interest-free money. New Zealand tertiary education also has a relatively minor role for need-based scholarships to cover the costs of study, policies that usually benefit people from modest income families.

These are major elements of our public service delivery, and in combination do not appear at all to be lined up to cater to low income people at the expense of high income people. High income New Zealanders are included in most forms of public services, often on better terms than they would receive in many other OECD countries.

So, what is to be done? When things as complex as “tax policies” or “government policies” are out of balance, there are myriad possible ways to address it. At a really broad level, we could more narrowly target social services, or increase some taxes on high income people, or do both to a more mild degree. For a long time, New Zealanders have been clear on what they prefer when given that particular choice. When offered the tradeoff between cutting back on public services or raising taxes, New Zealanders are more interested in keeping their public services inclusive and relatively free from user pays than in keeping current tax levels.